Let’s begin by watching the following video. Turkish Classical Music music probably sounds somewhat familiar to you in that you have heard it or music similar to it before earlier in this course. As you watch the video, consider some things:

Where have you heard music similar to this before?

What purpose might this type of music serve?

In this video specifically: what kind of instruments do you see/hear? How does the vocalizations of the singers sound different from what you might hear on the radio? What are the musicians wearing? How are they arranged physically? What about the music itself? What is striking you about the Rhythm/Melody/Harmony/Timbre/Dynamics/Texture/Form of the music that gives Turkish Classical Music its unique quality?

TÜRK SANAT MÜZIGI

TÜRK SANAT MÜZIGI | TURKISH CLASSICAL MUSIC (also known as Ottoman Classical Music) is a tradition of music developed by the nobility of the Ottoman Empire located in the Middle East from c. 1300-1923 CE. Because of its position in the north of the Middle Eastern peninsula, the country of Turkey is uniquely situated as a crossroads of trade, culture, and ideas.

Turkish Classical Music sounds like the combination of many other music types we have studied so far. Many of its traditions and practices are similar to that of Indian Classical Music. Its form is reminiscent of Western European Classical Music. The instruments are similar to those one would find in the rest of the Middle East, Northern Africa, Europe, and India.

While Turkish Classical Music holds its own unique identity, elements of its practices mingle with others from neighboring regions. In addition, it branches into both sacred and secular music with the secular side reserved for concert performances and the sacred side generally part of the SUFI religious tradition. Sufism is a mystic religious practice based in Islam that has a deep connection with music as a spiritual conduit, unlike mainstream Islam that generally considers music to be an unproductive pastime.

MAKAM/MAQAM

Similar to that of the Indian Raag, the Turkish MAKAM is a complex mode and melodic system utilized for the development of melodic content and improvisation.

Makams have many different patterns and these can change ascending versus descending and also between octaves (with the pattern not staying consistent from octave to octave). In addition, Turkish Classical Music uses SEMITONES or Quarter-Tones which are notes that exist between the Chromatic pitches on a Western piano. To Western-trained ears, these notes sound out-of-tune. While there are over a hundred Makams, only twenty are used with regularity. In addition, similar to the Carnatic/Hindustani view of Raag, Sufi mystics believe that each particular Makam mode can unlock or represent different moods or transcendent states of being.

USUL

Similar to that of the Indian Tala, the USUL is the Turkish rhythm system. The system is organized into a structure of strong and weak beats which repeat eventually over time but tend to have a lot of unevenness within the sequence before repeating. Subdivision of beats and weak versus strong are verbalized with the following syllables:

DÜM

DÜ-ÜM

TEK

TEKKYAA

TEKE

TE-EK

FASIL

The format of Turkish Classical Music is highly structured with one of the most popular and iconic formats being the FASIL. The Fasil is a musical SUITE (a collection of short, related pieces performed in a specific order) that generally includes several instrumental pieces at the beginning and end and several vocal pieces in the middle. Most Fasil are 60-90 minutes in length. A typical Fasil may look like this:

TAKSIM: An improvised instrumental prelude

PETREV: A group instrumental piece involving long rhythmic cycles

SARKI: An art song with a vocalist and lyrics

YÜRÜK SEMÂ’Î: A piece usually in compound meter that accelerates throughout

TÜRK AKSAGI: A vocal piece usually in 5/4 or 5/8 (which are uneven, MIXED METERS; 2+3)

TAKSIM: Another improvised instrumental interlude

SARKI: Another art song with a vocalist and lyrics

SAZ SEMÂ’Î: A fast instrumental finale in compound meter

INSTRUMENTS

BENDIR

The BENDIR is one of several drums often found in Turkish Classical Music. Generally, there is only one drummer per ensemble as the complexity of the drum’s rhythm would clash if generated by multiple drummers. The Bendir is a FRAME DRUM meaning it features a somewhat loose drumhead attached to a wide circular frame. The looseness of the head allows the performer the ability to adjust the tensions with pressure from the fingers and palms, resulting in a multitude of pitches and sounds from the same instrument.

KEMENCHE

The KEMENCHE is a spike fiddle that is a bowed string instrument similar to orchestral string instruments. The Kemeneche is played with the body of the instrument on the player’s knee and the neck projecting upward. Its timbre is hollow, thin, and flat.

NEY

The NEY is a end-blown flute constructed from hollow cane or reed. While most end-blown flutes generate their sound with a fipple (a duct near the mouthpiece like the recorder has), the Ney takes a technique similar to the transverse Western Classical flute where the player sends their airstream into open space with some of the air catching against the Ney’s mouthpiece and splitting off down into the flute. The Ney is used in many Middle Eastern traditions of music and is specifically prevalent in Egyptian music. Its timbre is breathy, airy, and light. The Ney is generally the only wind instrument found in most Turkish Classical Ensembles.

OUD

The OUD is an ancient instrument and is considered by many to be the main instrument of the Turkish Classical Music tradition. It is an early predecessor to the guitar and lute and it is played with a pick. Unlike the guitar, this string instrument has a bowled back and no frets on the fingerboard. It has 11 or 13 strings in pairs with the exception of the lowest string. It also has a 90 degree bend in its neck at the nut. The Oud is rich, deep, and resonant.

TANBUR

The TANBUR is another string instrument that is played with a pick like the Oud. It has a round body and an extremely long neck compared to other string instruments. In the Middle East, there are many styles and types of Tanbur, and the Turkish Tanbur is unique. The sound of the Turkis Tanbur is vibrant, round, and heavy.

MUSICAL ELEMENTS OF TURKISH CLASSICAL MUSIC

RHYTHM: Rhythm is generally more complex than Western Classical and popular music consumers are familiar with because of meter. The meters of Turkish Classical Music are based on complex series of strong and weak beats in uneven patterns called Usul. While all instruments and vocalists participate in rhythm, the percussionists are most responsible for delivering complex beat and pulse.

MELODY: Melodies are based on Makam which are similar to Western Classical scales, only more complex because of the use of semitones, different patterns ascending and descending, and different patterns for each octave of a mode.

HARMONY: Western-style harmony does not exist in Turkish Classical Music as all instruments and vocalists performing on a piece are playing versions of the same melody. Because of this heterophonic texture, there is never purposeful harmony created by instruments and voices in a way that creates purposeful intervals and chords like in other music traditions.

TIMBRE: There is not a specific encompassing timbre of a Turkish Classical Music ensemble. This is first and foremost because ensembles vary in number of musicians and types of instruments and voices. In general, the Oud is often an important and grounding member of most ensembles and its rich, deep tone permeates the texture of other instruments. The vocal timbre of Turkish Classical singers is generally full, clear, and slightly nasal without vibrato; however, tending to use a wide, warbling melodic ornamentation.

DYNAMICS: There is not a consistent dynamic mode to speak of in Turkish Classical Music. Music can be loud or soft and can grow louder or grow softer during a single piece. In general, music is louder at a faster tempo and/or when more instruments are involved and softer at a slower tempo and/or when less instruments are involved.

TEXTURE: What is perhaps most striking and easily discernible about Turkish Classical Music is its heterophonic texture. In each piece of music, different combinations of instrumentalists will play the same exact learned melody but improvise over it with slight ORNAMENTATION at the same time in order to achieve a heterophonic texture. Each instrumentalist is playing their own variation of the same melody at once.

FORM: Form for individual pieces are based on the rhythmic patterns of the established Usul for the piece. Usul can vary from very short in length (such as four beats) to very long in length (such as 30 beats) before the pattern repeats itself. Another important aspect of Turkish form is the larger structures of pieces paired or ordered into suites such as the Fasil.

CONSERVATORY TRAINING

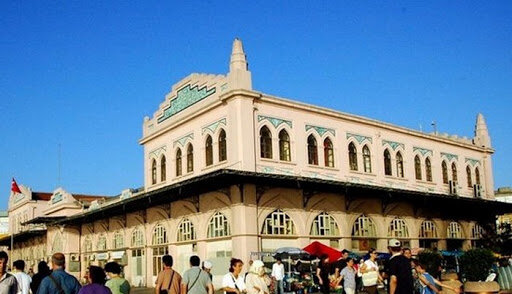

Turkish Classical Music is highly structured and formalized, developing for centuries by the noble class of the Ottoman Empire. Unlike many music traditions of the world, the Turkish system of CONSERVATORY training is similar to that of Western Classical Music conservatories in Europe and the United States. In a Conservatory setting, students train in school from a young age to become a professional musician. They attend private lessons with skilled teachers on their instruments and also classes to help with music theory, music history, ensemble performance, and training with improving musicianship. The largest of these schools in Turkey is the Istanbul University State Conservatory located in Istanbul (the capital of Turkey).

Turkish Classical Music also has its own written music notation system called HAMPARSUM but the system is relatively unused today in favor of the Western Classical music notation system. The notation system was developed by 18th century Armenian musician and music theorist, Hampartsoum Limondjian. While most Western musicians do not learn or understand Turkish Classical Music, most Turkish Classical Musicians are trained in both styles - so reading one notation system helps with consistency.

WHERE TO HEAR TURKISH CLASSICAL MUSIC IN THE USA

Turkish/Ottoman Classical Music Concerts

Middle Eastern Cultural Festivals

Middle Eastern Community Centers

Middle Eastern Restaurants